A Year in Words: The Ulster Language and Dialect Archive

Project Archivist Niamh Dolan writes about 'Unlocking Ulster’s Languages Archives’, a National Museums NI project, funded by ‘Archives Revealed’, a partnership programme between The National Archives, the Wolfson Foundation and the Pilgrim Trust.

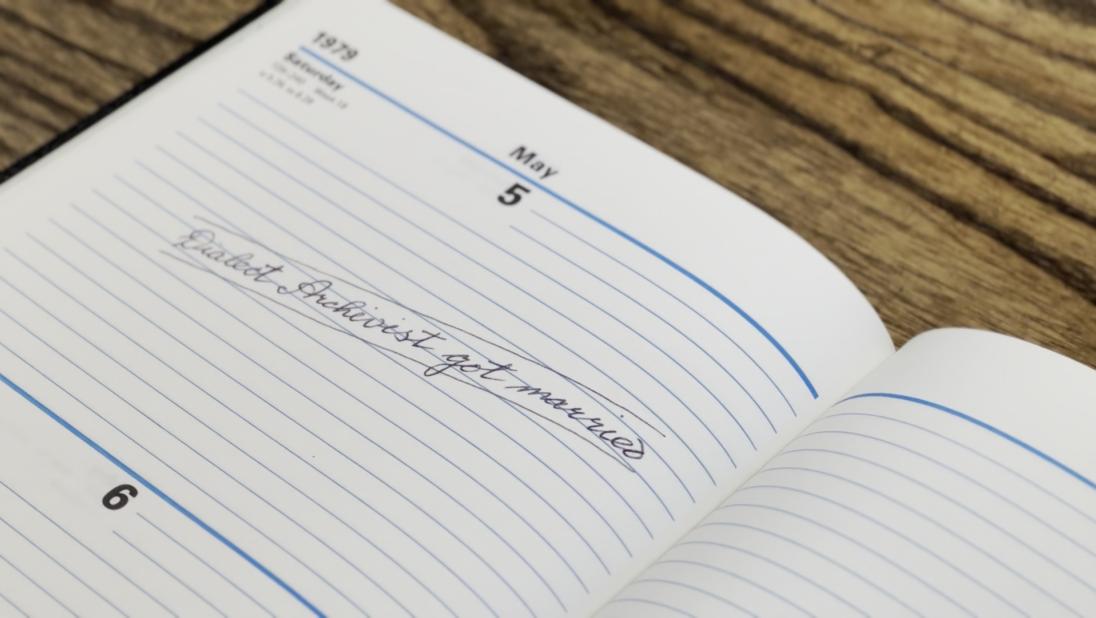

Over the past year, I’ve tackled the unique task of ‘Unlocking Ulster’s Languages Archives’. That’s the name of the project on which I worked at National Museums NI, funded by an ‘Archives Revealed’ grant from The National Archives.

As project Archivist, I catalogued the material contained within the impressive Ulster Language and Dialect Archive at the Ulster Folk Museum.

You’d be pardoned if you were to say you weren’t aware of this archive. You might also be surprised to learn that it has been a central part of the collections at Cultra since the very formation of the museum.

For various reasons, this archive had lain quite dormant, essentially untouched and scarcely promoted, for several years.

The ‘Archives Revealed’ grant changed all of that. My role in ‘unlocking’ these collections has enabled them to play a part in the overall ‘Reawakening’ of the Ulster Folk Museum.

Ulster Language and Dialect Archive

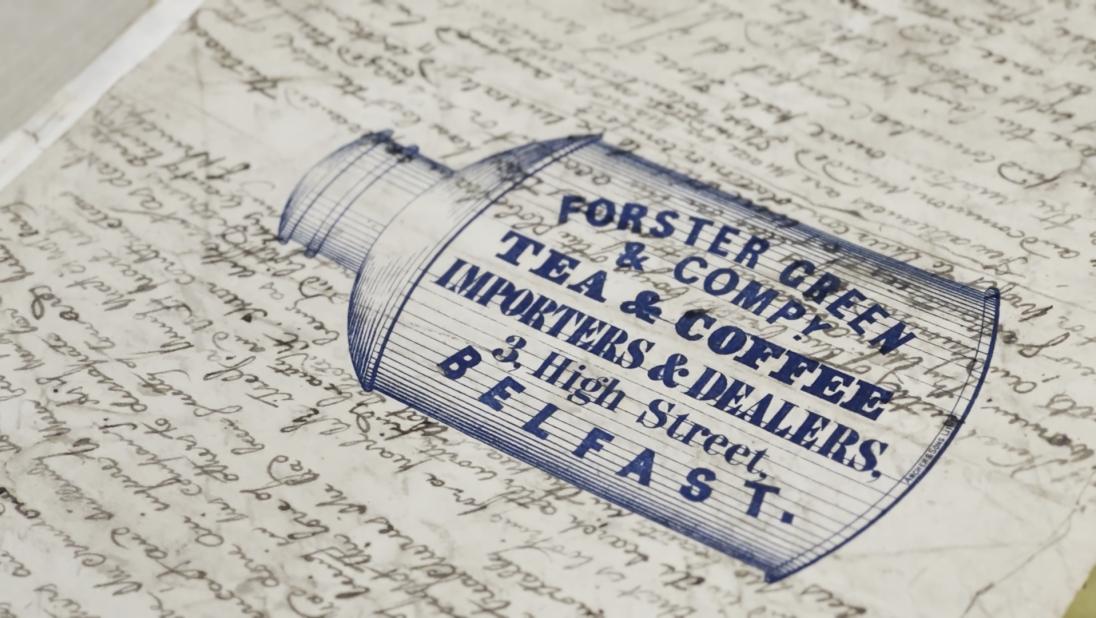

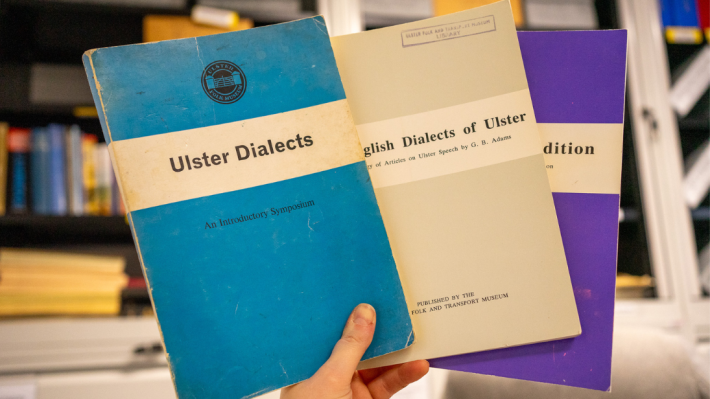

The Ulster Language and Dialect Archive today showcases the linguistic diversity of the patterns of local speech in Ulster which comprises Irish Gaelic, Ulster-Scots and Northern Hiberno-English.

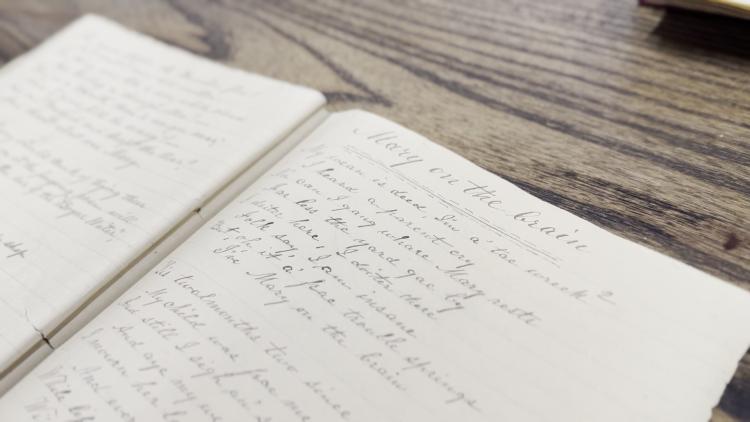

Its origins can be traced to the 1950s, when members of the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club began a project to compile an Ulster Dialect Dictionary.

As the Ulster Folk Museum concept took shape from 1959, Brendan Adams, a Field Club member, suggested the materials gathered be handed over to the Museum and form the basis of an Ulster Dialect Archive. This was agreed to and Adams became Honorary Archivist. He officially joined the Museum staff as Dialect Archivist in 1964. A polyglot and prolific letter-writer, he wrote correspondence in at least eight different languages.

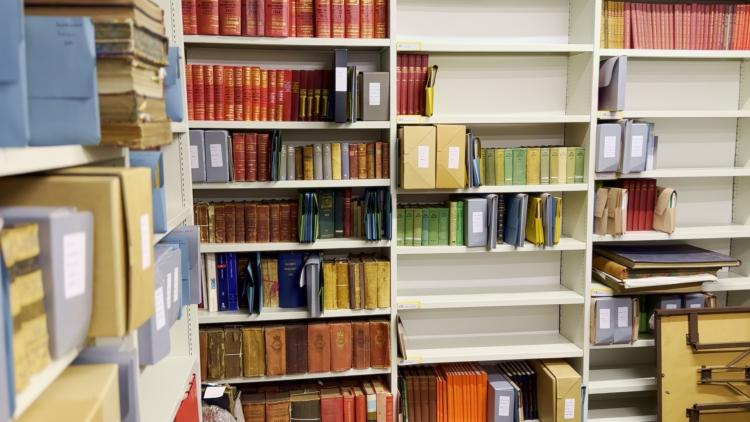

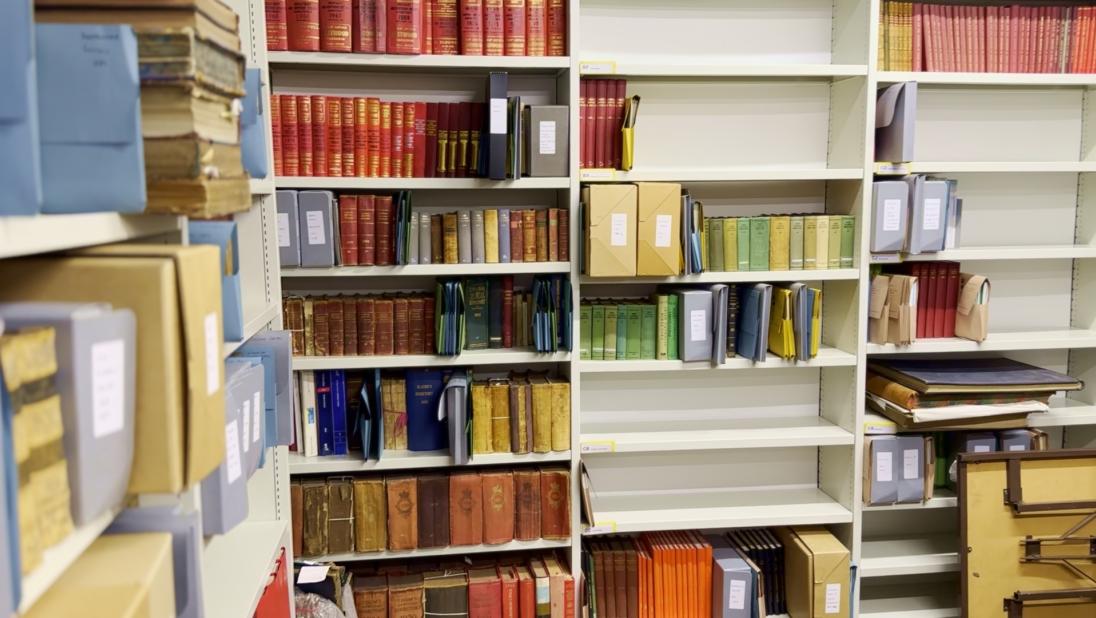

During his tenure up to his death in 1981, and indeed in subsequent years, the collections expanded to include a selection of books, and a mixture of handwritten manuscripts, glossaries, correspondence and numerous other items from nine separate collections.

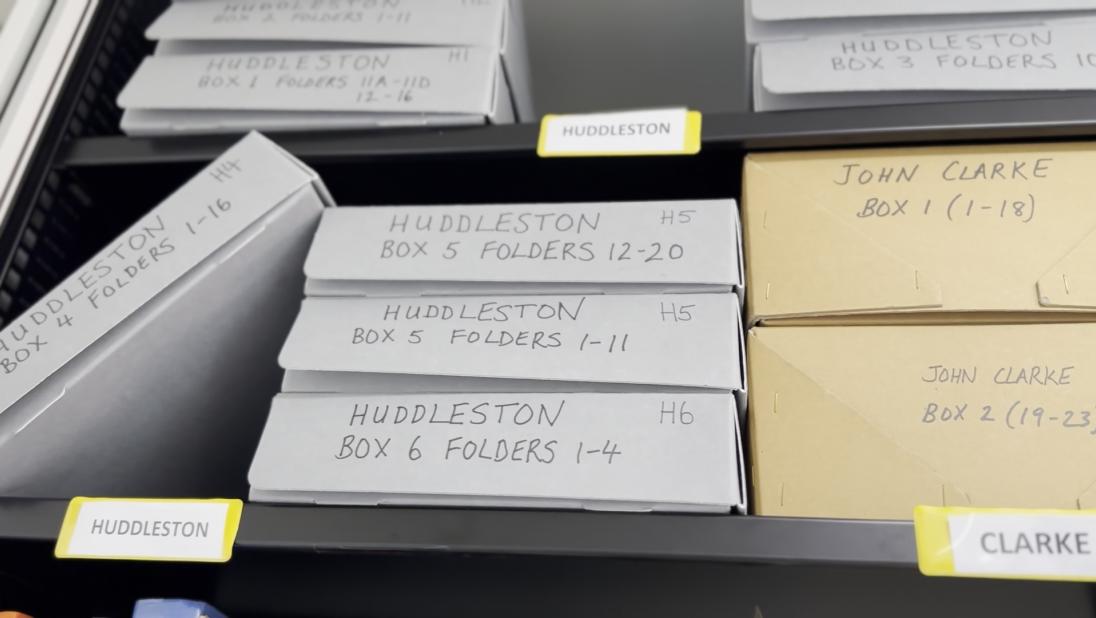

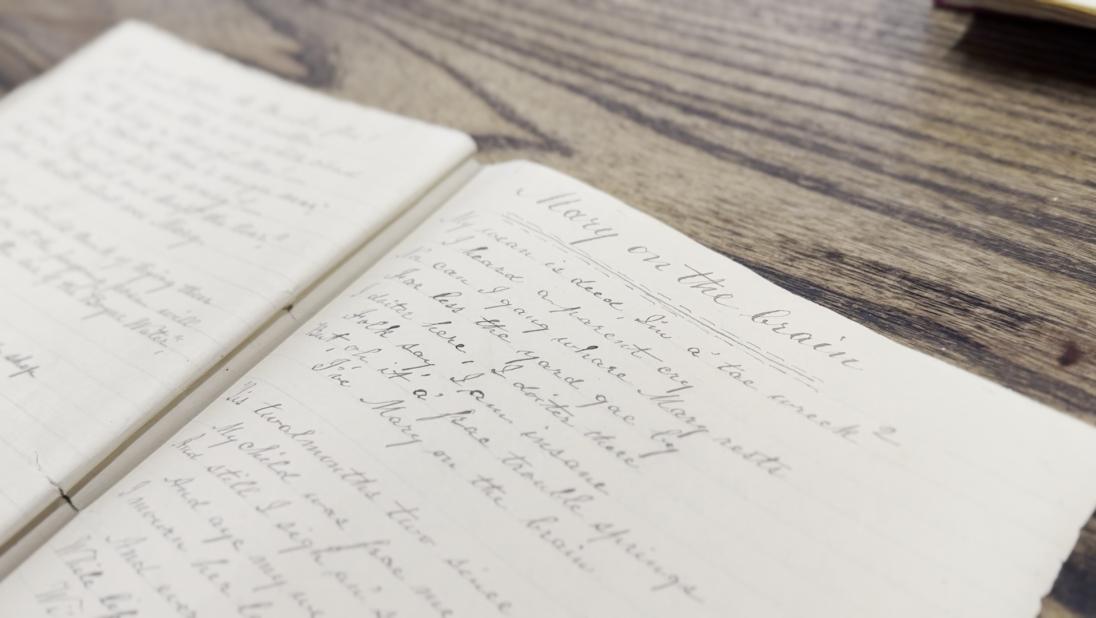

Foremost among the collections are the papers of the following figures: Robert Huddleston (1814-1887); Sir John Byers (1853-1920); Robert Lee Moore (1862-1946); Matthew Montgomery (1874-1959) and his son Robert Hanna Montgomery; William F. Marshall (1888-1959); Robert J. Gregg (1912-1998); Brendan Adams (1917-1981); the Ulster-Scots research notes of former members of Library staff; and John Clarke, who recently donated his thesis concerning the dialect of south Derry.

Behind the scenes at the Library & Archives

My Work on the ‘Archives Revealed’ Project

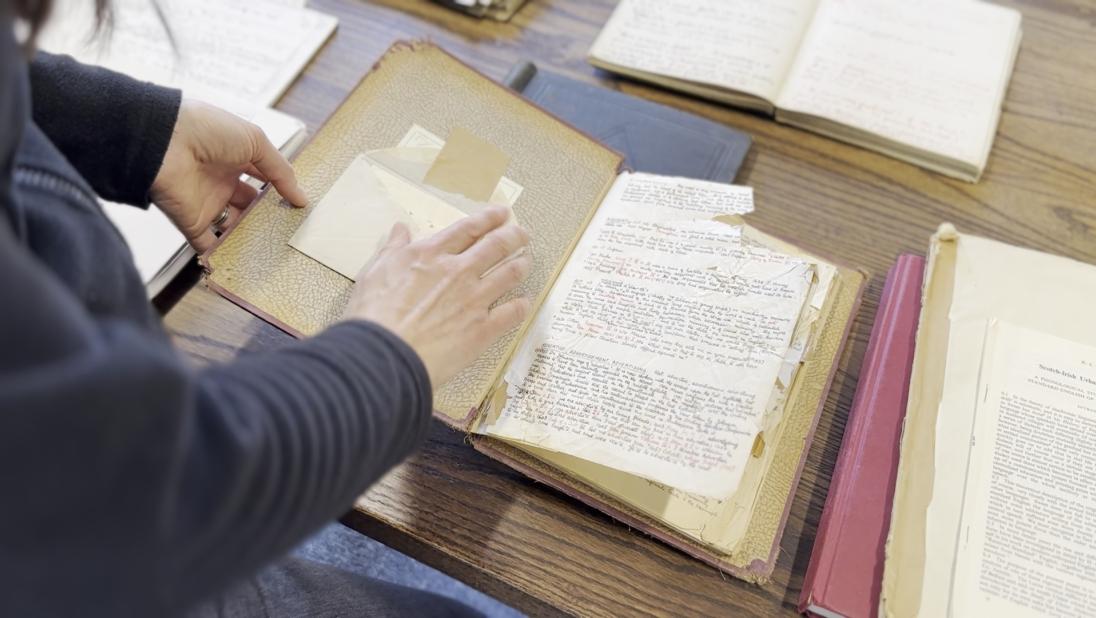

I began work as Archivist on 2 March 2023. Upon assessment, the extent of the Ulster Language and Dialect Archive proved greater than I initially thought.

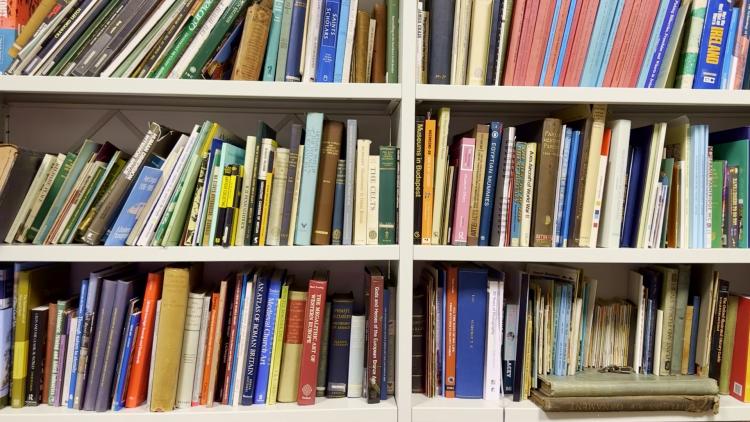

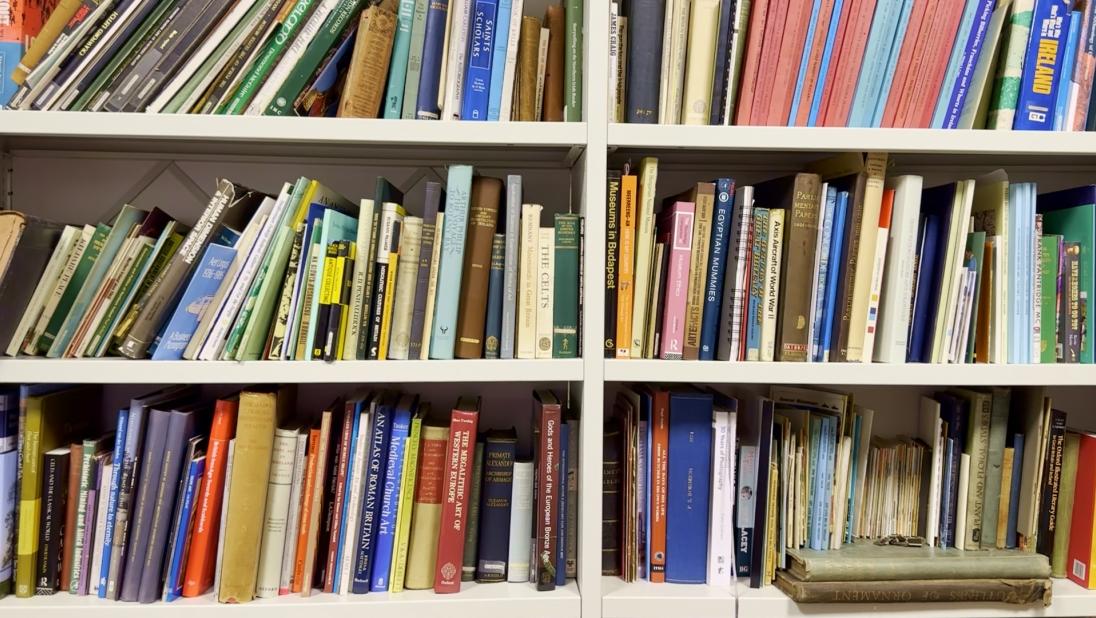

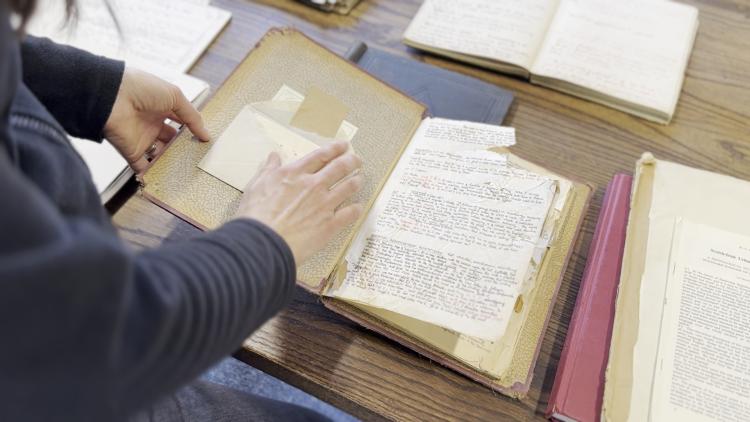

The Research Room that I worked in contained over fifty archive boxes and two ceiling-high cabinets full of material. Having looked inside the boxes and sifted through the cabinet files, I realised this would be a challenging task to complete within a year. I prioritised the material that was significant and catalogued it first, and in the process I reorganised the entire Archive and made is easier to locate items.

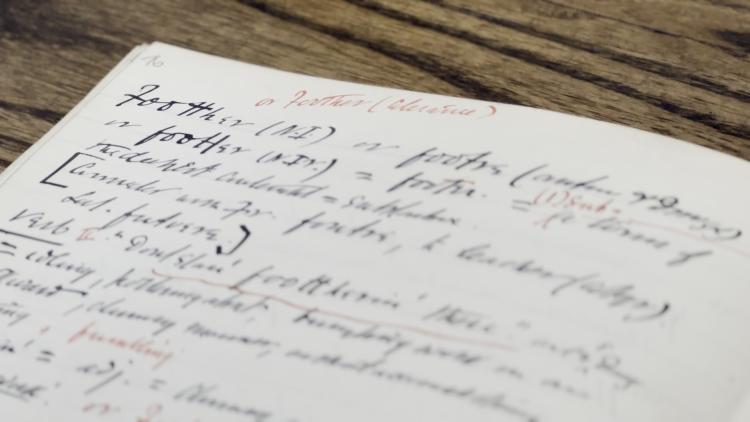

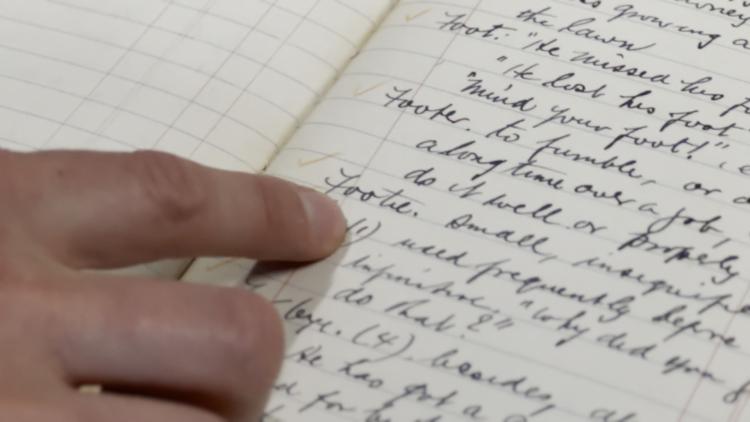

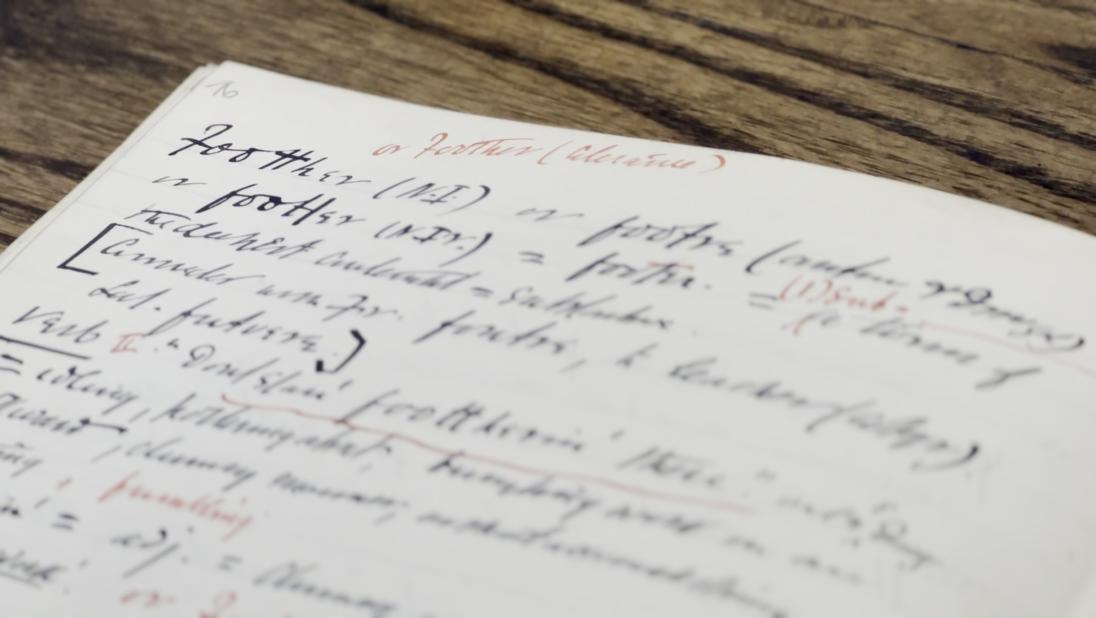

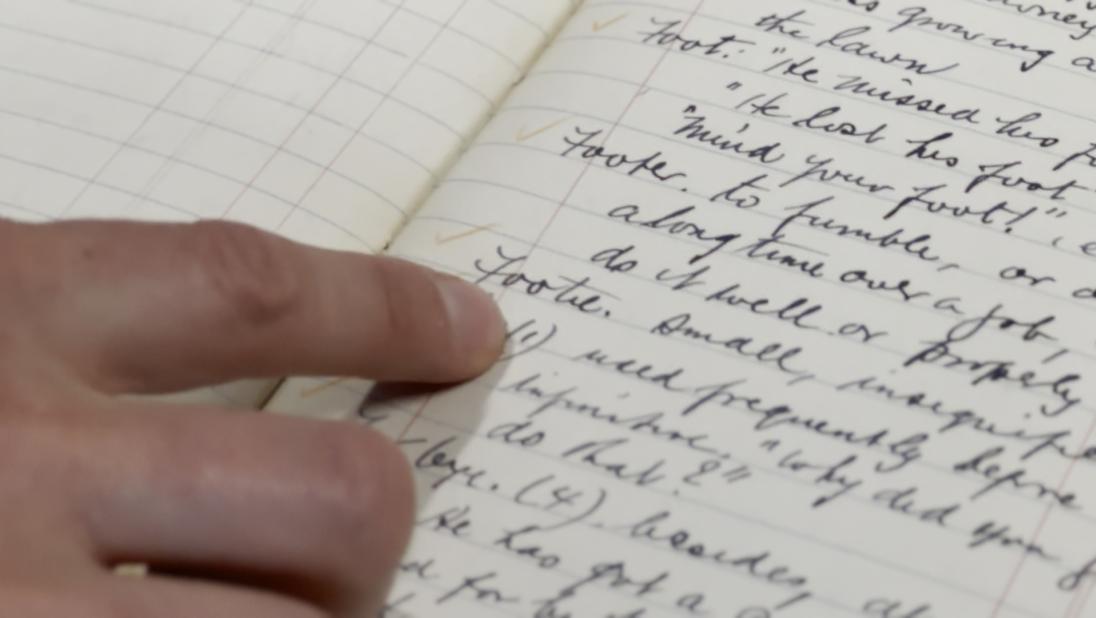

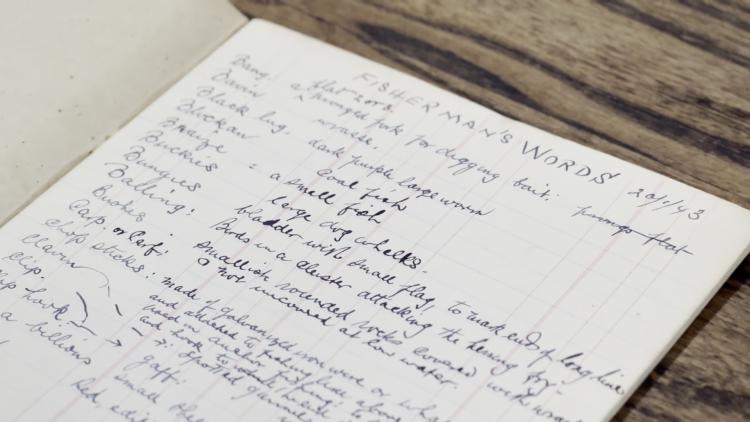

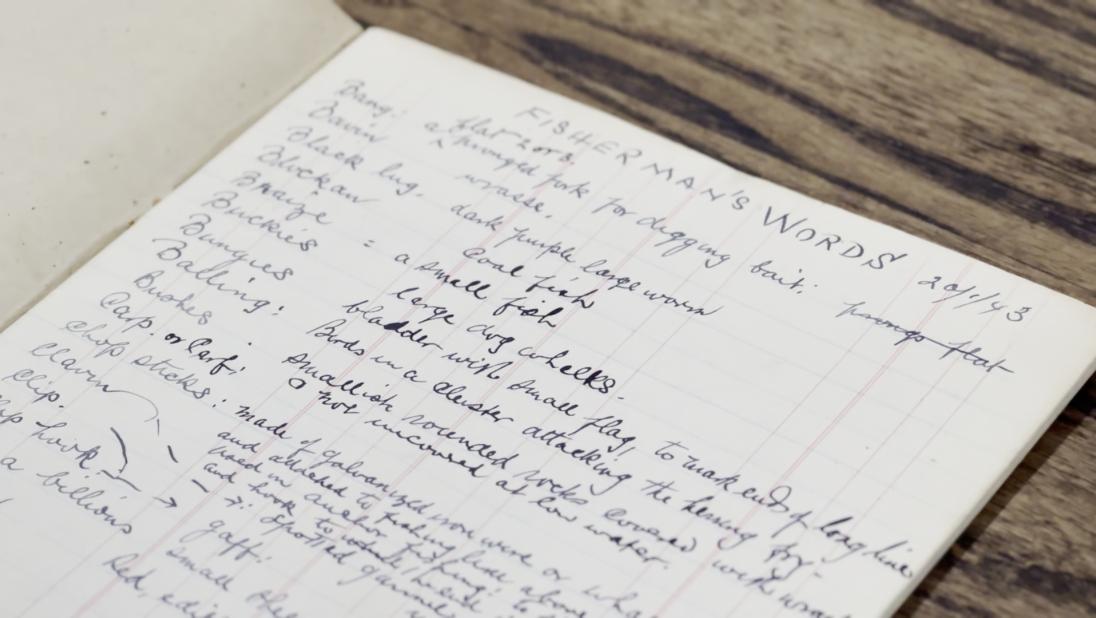

As a person not from Ulster, my awareness of local Ulster dialect words is more heightened as I notice the unfamiliar words that would not feature in typical conversations from my home area. The numerous glossaries in the Ulster Language and Dialect Archive are overwhelming, containing words from every corner of Ulster, rich in their variety. ‘Footer’, for example, is a word I had not previously encountered, but now I hear it regularly used throughout Ulster. The word is found in the majority of the glossaries within the Archive.

Footer in the Collection

Brendan Adams Papers

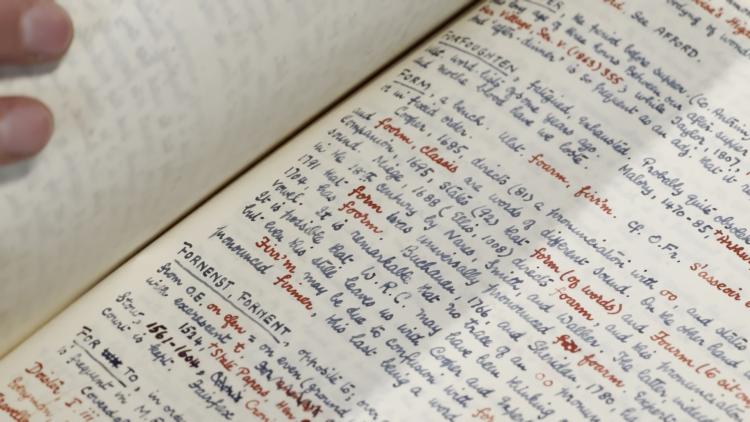

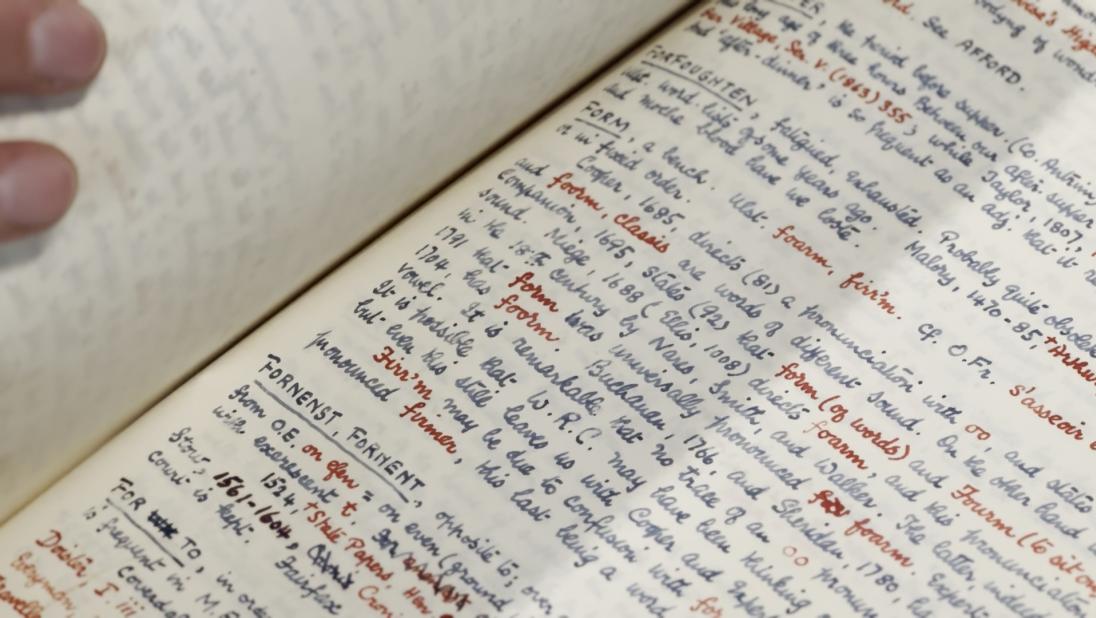

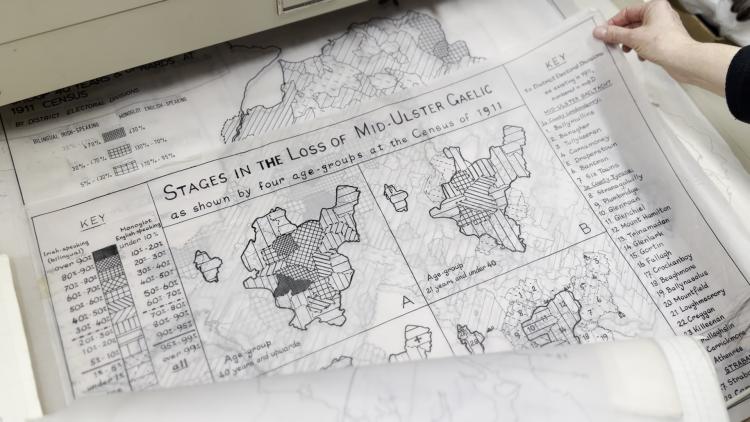

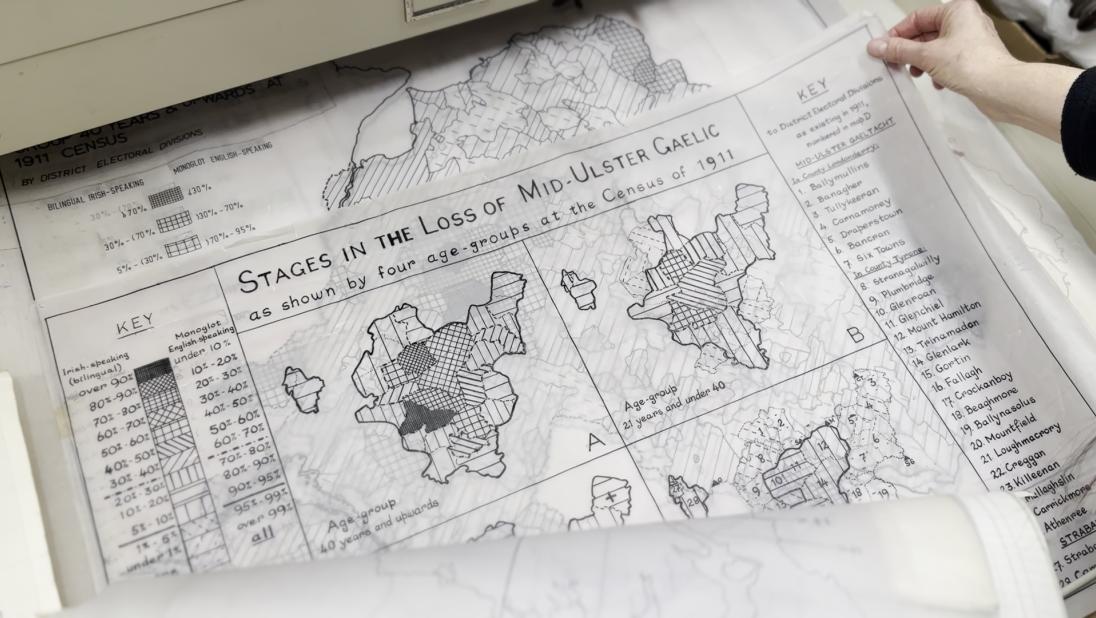

The main focus of my cataloguing work was given to Brendan Adams’ papers, as the biggest single collection. They encompass a mixture of research notes, correspondence, diaries and linguistic maps, and contained important information regarding the history and development of the Ulster Language and Dialect Archive itself.

The extensive Adams collection that had been in the Archive for years was augmented by the donation of three further boxes of papers, courtesy of his daughter, Angeline Adams, shortly before the start of the project

Cataloguing Adams’ material enabled me to understand his personality and thinking. He was extremely detailed in his research and letters. I really enjoyed reading his personal letters to family members as they displayed the kind and caring man he was and how passionate he was about his work. He was an extremely busy man who was involved in numerous committees and boards. He attended conferences and seminars, mixing with linguistic experts from around the world and gave talks on his latest research. But he also shared his knowledge with local societies and groups who booked him months in advance to speak at their meetings.

Adams’ enduring legacy to the Museum can be found not only in his manuscript collections, but also in the Sound Archive. He was the first curator at Cultra who used a tape-recorder, principally to record local accents, and he became one of the chief architects of the Tape-Recorded Survey of Hiberno-English Speech – a massive collection of 539 interviews with people from every county of Ireland, recorded between 1972 and 1981. While I did not have any part in cataloguing items from the Sound Archive over the last year, this is a very significant collection and worth highlighting as a complement to the papers.

The Collection

Public Engagement

The cataloguing of the Ulster Language and Dialect Archive forms a key part of National Museums NI’s ‘Languages of Ulster’ programme by enabling access to this unique collection to a wide audience. Located within the newly refurbished Library at the Ulster Folk Museum, it has seen a significant number of visitors throughout the past year from local historical groups, Ulster-Scots enthusiasts, the National Folklore Collection UCD staff, and researchers.

The cataloguing metadata that I compiled is planned to be added to National Museums NI’s collections information system in the coming months, and as such it should become publicly searchable online before long.

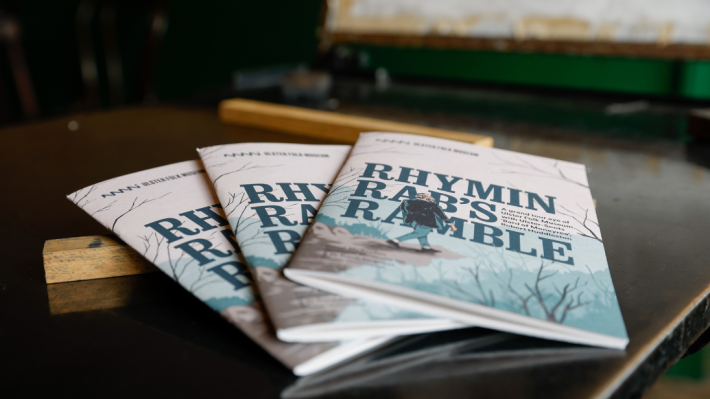

A programme which showcased the handwritten manuscripts of Huddleston was broadcast on Belfast local television (NVTV), and a Huddleston Ulster-Scots trail of the Ulster Folk Museum is due to be launched in May. The Museum’s digital content team also recently recorded me speaking in depth about the Ulster Language and Dialect Archive, which is to be promoted on National Museums NI’s website and should encourage further visitor engagement.

I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to work on such an interesting and diverse Archive and am privileged to have gained a deep knowledge through engaging with the various collections. Although I did not get to catalogue the entire Archive, I catalogued almost 7,500 items, which are searchable on a document. The Ulster Language and Dialect Archive is a hidden treasure within the Library and Archives at the Ulster Folk Museum and it was a pleasure to showcase its material and talk about its value to visitors.

Explore More

Ulster Dialects At Sixty

Dónal McAnallen, Library & Archives Manager, reflects on 60 Years of the Ulster Dialect Archive.

Rhymin Rab’s Ramble

An educational, self-guided tour exploring the story of the Ulster Scots language with 'Bard of Moneyrea', Robert Huddleston

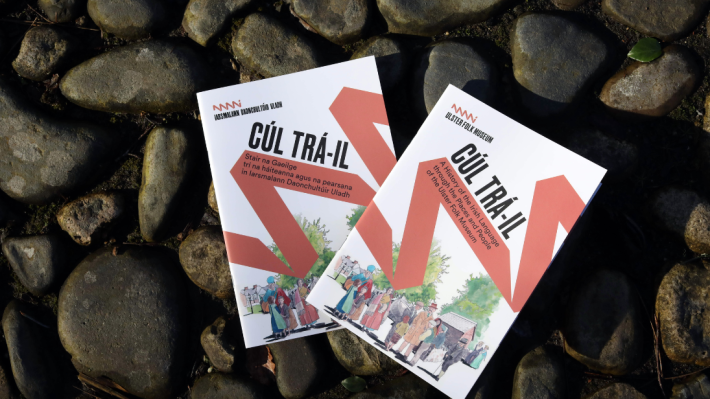

Cúl Trá-il

An educational, self-guided tour of the museum exploring the story of the Irish language through the places and people of Ulster Folk Museum