Lacemaking

Bobbin Lace

One of the earliest records of a lace manufacturer in Ireland is Mathew Phillips of Dublin, recorded in 1638 as a maker of lace worked on a pillow, with bobbins made of bone. The terms bone lace, bobbin lace and pillow lace are synonymous – used to describe a type of work produced by plaiting threads around pins on a supporting pillow, using thread wound around bone or wooden bobbins.

In the 1700s the Royal Dublin Society supported the work of the Irish bobbin lace industry at home and abroad by offering premiums. Recipients of these awards included the McClean sisters of Markethill, Co. Armagh, in 1742.

Lace schools In Ireland, established in the 1850s, employed teachers from England and Belgium to instruct young women in bobbin lace techniques. During harsh years of famine in Ireland during the 1800s, many women produced lace in their own homes as ‘relief work’, requiring only a pillow, bobbins and thread.

A bobbin lace school established in 1893 at Springhill House in Limavady, Co. Londonderry employed local women to work for the ‘Ballykelly Lace School’, which lasted for around ten years.

In the early 1900s, the lacemaking and white work embroidery industries employed many tens of thousands of women across Ulster as ‘outworkers’ producing high quality needlework. However, bobbin lace was labour intensive and struggled to compete with the machine-made laces that were widely available from the 1880s onwards.

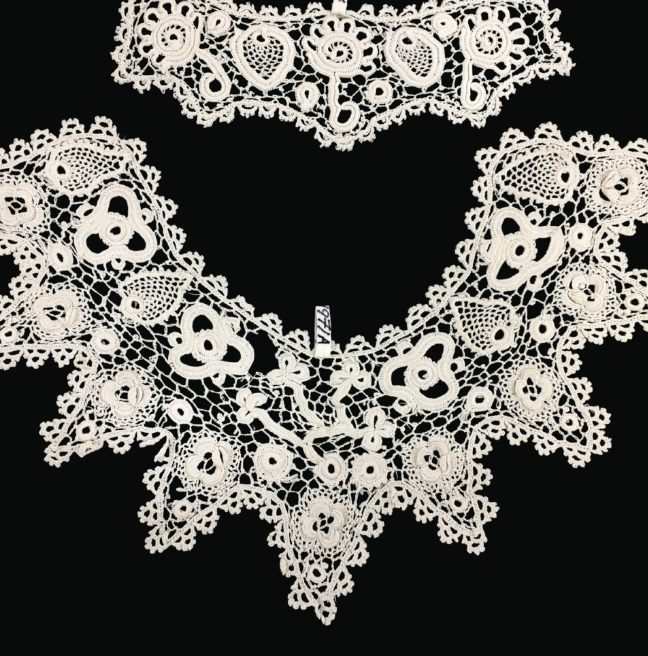

Crochet lace

Crochet lace is strongly associated with Ireland. At the height of its popularity in the mid to late 1800s, it was known across Europe as ‘Point d’Irlande’. It is worked in fine white cotton thread with a crochet hook, linking individually made motifs together with a background grid of bars, also known as ‘brides’.

This technique developed after the 1846 publication of the first book of Irish Crochet patterns, based on earlier examples of Venetian needle lace. Convent schools in and around Cork supported the teaching of this technique. Requiring only a steady supply of cotton yarn and a simple crochet hook, this work enabled many rural households to weather tough times, with whole families of women engaged in producing fine collars and trims for good quality table and bedlinens.

The finished work was marketed across the world through a huge network of agents and retailers. One of the best known was Robinson and Cleaver, a Belfast department store that gained a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria for its Irish linens and laces.

From the 1920s, as manufacturers produced work imitating crochet lace at a fraction of the cost, the industry declined drastically. The exception of crochet lace collars and cuffs used on Irish dance dresses from the 1930s until relatively recently.

Carrickmacross Lace

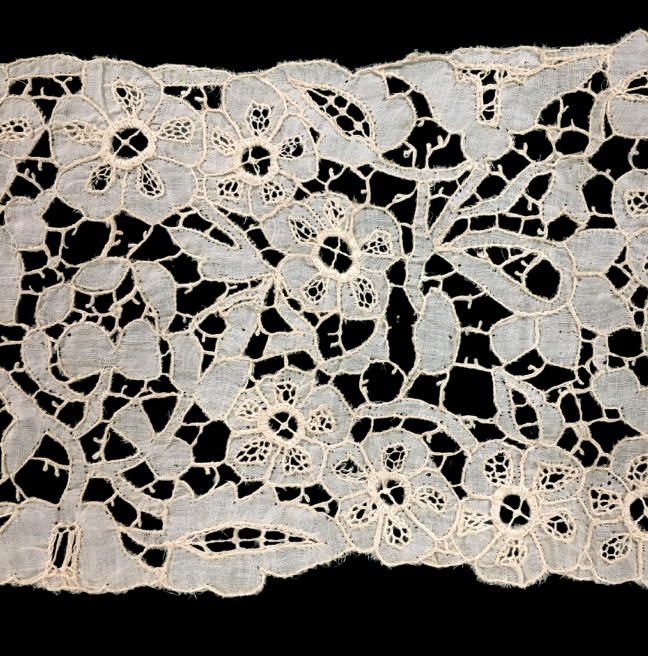

Carrickmacross lace shares characteristics and techniques associated with European laces of the 1700s and early 1800s. It is a style of needle lace, with a fine cambric cloth hand-stitched to a net background.

The pattern is outlined on the fabric surface with a heavy thread couched in place, the excess or ‘background’ fabric carefully cut away to reveal the applique design which is then enhanced with decorative filling stitches and ‘pops’ – small circular motifs. The filling stitches and a picot stitched edging are among the characteristics of traditional designs for Carrickmacross lace.

This type of lace is believed to have originated in the village of Donaghmoyne, near Carrickmacross in County Monaghan in the 1820s, promoted by Mrs Grey Porter. Using examples of lace collected in Italy during her honeymoon in 1816, she adapted the designs and techniques to provide much needed employment for young women in the local area.

Carrickmacross lace proved to be commercially successful, due in part to the availability of machine made net. It was a popular choice for wedding veils, fine handkerchiefs, and for flounces to trim vestments in the Roman Catholic Church.

Limerick Lace

Limerick lace is technique that is worked by hand stitching on a background of fine net. The patterns are achieved by ‘darning’ decorative embroidery stitches into the net background, working over the motifs with additional filling stitches to achieve depth of pattern.

Limerick lace was established as a commercial enterprise. A lace factory opened in Limerick around 1843, employing a number of local women who had previously been employed by the glove making industry. At its height the industry employed up to 3,000 workers, and its output eclipsed that of equivalent English lace makers of the time.

The success of Limerick lace in the late 1800s is due to Florence Vere O’Brien, originally from England, who settled in Limerick after marriage. She promoted improvements in design, workmanship and quality of materials to increased commercial and artistic acclaim.

The development of increasingly sophisticated machine-made laces, many of them imitating the styles of Limerick lace, led to a decline in the industry from around 1900.

Like Carrickmacross lace, Limerick was a popular choice for wedding veils, christening robes, fine collars and cuffs, and religious vestments.

Lacemaking Today

Today the craft of lacemaking is carried on by members of craft guilds and groups. The Lace Guild of Northern Ireland has been associated with the museum for over 40 years and its members have been regular volunteers.

Their continued support for this work and their participation in events and activities at the museum are helping to ensure that lace making will continue to thrive in future.